Beekeeping

Bush Bees Home

Lifecycle of a Bee

Castes

Queen

Queenlessness

Supersedure

Swarming

Worker

Drone

Yearly cycle of the colony

Winter

Spring

Summer

Fall

Products of the hive

Bees

Larvae

Propolis

Wax

Pollen

Pollination

Honey

Royal Jelly

Click on Thumbnails for bigger pictures

english, español, deutsche, français, português, русском, română, polsku, беларускай,

Bee Basics

In order to do beekeeping, you need a basic understanding of their life cycle and their yearly "colony" cycle. You have two organisms. The individual bee (which can't exist as an organism for very long) and the colony superorganism.

Lifecycle of a bee

Bees are one of three main castes. Queen, worker or drone. The queen is the one bee that reproduces, but even that she can't do by herself. She is the one bee that goes out and mates, during one period of her life, that lasts a few days, and then she lays eggs for the rest of her life. The workers, depending on their age, feed brood, make comb, store honey, clean house, guard the entrance or gather honey, pollen, water or propolis. The drones spend their days flying out to drone congregation areas (DCAs) in the early afternoon and flying home just before dark. They spend their lives in hopes of finding a queen to mate with. So let's follow each cast from egg to death:

Queen

We will start with the queen since she is the most pivotal of any bee because there is only one of her. The reasons the bees raise a queen are: queenlessness (emergency), failing queen (supersedure), and swarming.

Queenlessness

The cells for each appear slightly different or at least occur under different conditions that can be observed. A queenless hive will have no queen that can be found, little open brood and no unhatched eggs. The queen cells resemble a peanut hanging on the side or bottom of a comb. If the queen died or was killed the bees will take a young larvae and feed it extensive amounts of Royal Jelly and build a large hanging cell for the larvae.

Supersedure

In supersedure the bees are trying to replace a queen they perceive as failing. She is probably 2 to 3 years old and not laying as many fertile eggs and not making as much Queen Mandibular Pheromone (QMP). These cells are usually on the face of the comb about 2/3 of the way up the comb.

Swarming

Swarm cells are built to facilitate the reproduction of the superorganism. It's how the colony starts new colonies. The swarm cells are usually on the bottom of the frames making up the brood nest. They are usually easy to find by tipping up the brood chamber and examining the bottom of the frames.

The larvae that make a good queen are worker eggs that just hatched which happens on day 3 1/2 from the day the egg was laid. On day 8 (for large cell) or day 7 (for natural sized cells) the cell will be capped. On day 16 (for large cell) or day 15 (for natural sized cells) the queen will emerge. On day 22, weather permitting, she may fly. On day 25, weather permitting, she may mate over the next several days. By day 28 we may see eggs from a new fertile queen. From that time on, she will lay eggs (weather and stores permitting) until she fails or swarms to a new location and starts laying there. The queen will live two or three years in the wild, but almost always fails by the third year and is replaced by the workers. In a swarm the old queen leaves with the first (primary) swarm. Virgin queens leave with the subsequent swarms, which are called afterswarms. There are, of course, exceptions. Jay Smith had a queen that was still laying well at 7 years named Alice, but three years seems to be the norm when the bees replace them.

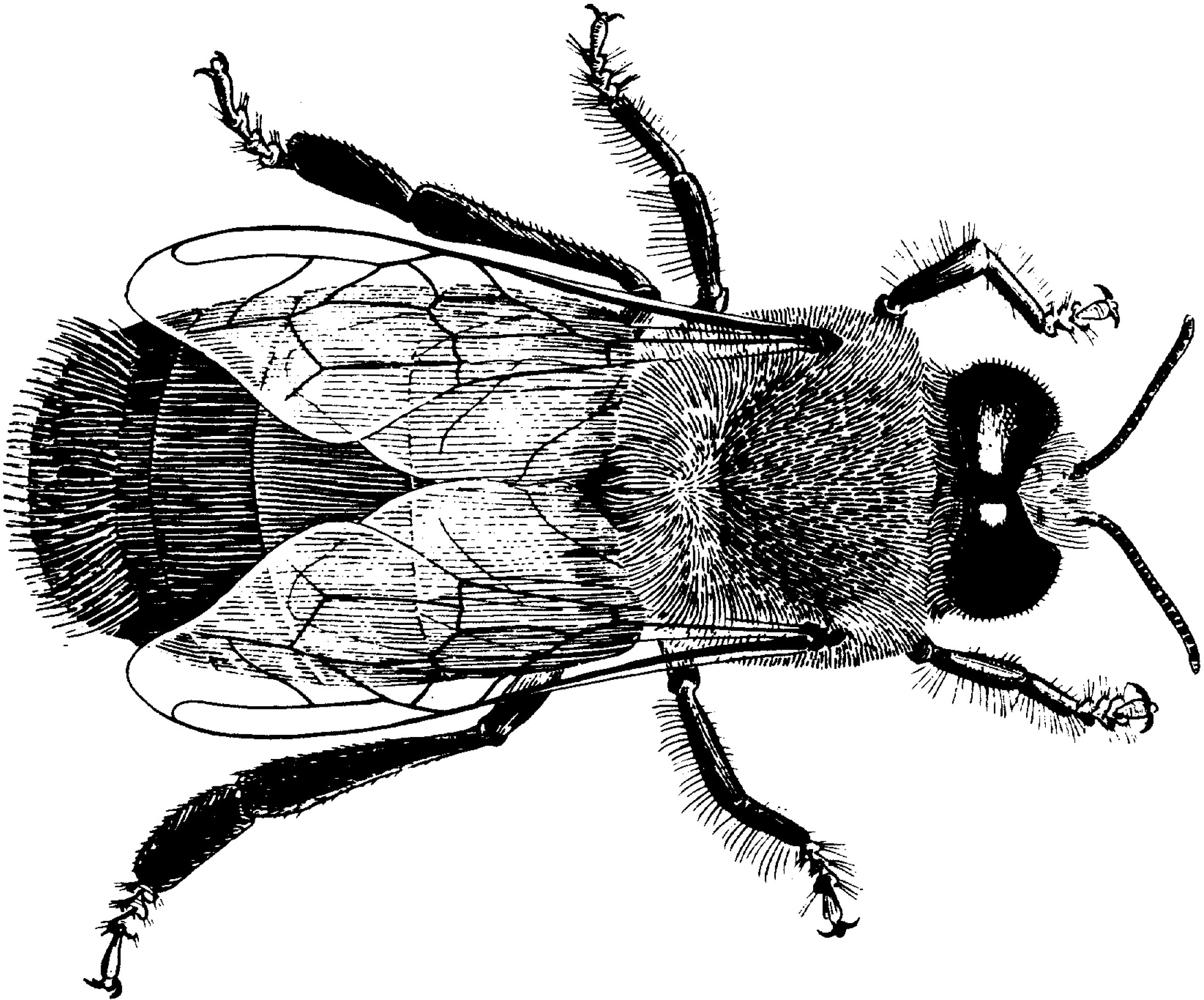

Worker

A worker egg starts out the same as a queen egg. It is a fertilized egg. Both are fed royal jelly at first, but the worker gets less and less as it matures. Both hatch on day 3 1/2 but the worker develops more slowly. From day 3 1/2 until it is capped it is called "open brood". It is not capped until the 9th day (for large cells) or the 8th day (for natural sized cells). From the day it is capped until it emerges it is called "capped brood". It emerges on the 21st day (for large cells) or the 18th or 19th day (for natural sized cells). From when the bees start chewing through the caps until they emerge they are called "emerging brood". After emergence a worker starts it's life as a nurse bee, feeding the young larvae (open brood). For the first 2 days the newly emerged worker will clean cells and generate heat for the brood nest. The next 3 to 5 days it will feed older larvae. The next 6 to 10 days it will feed young larvae and queens (if there are any). During this period from 1 to 10 days old it is a Nurse Bee. From day 11 to 18 the worker will make honey, not gather but ripen nectar and take it from field bees bringing it back, and build comb. From days 19 to 21 the workers will be ventilation units and guard bees and janitors cleaning up the hive and taking out the trash. From day 11 to 21 they are House Bees. Day 22 to the end of their life they are foragers. Except during winter, workers usually live about six weeks or less, working themselves to death until their wings are too shredded to fly. If the queen fails a worker may develop ovaries and start to lay. Usually these are drone eggs and usually there are several to a cell and they are in worker cells.

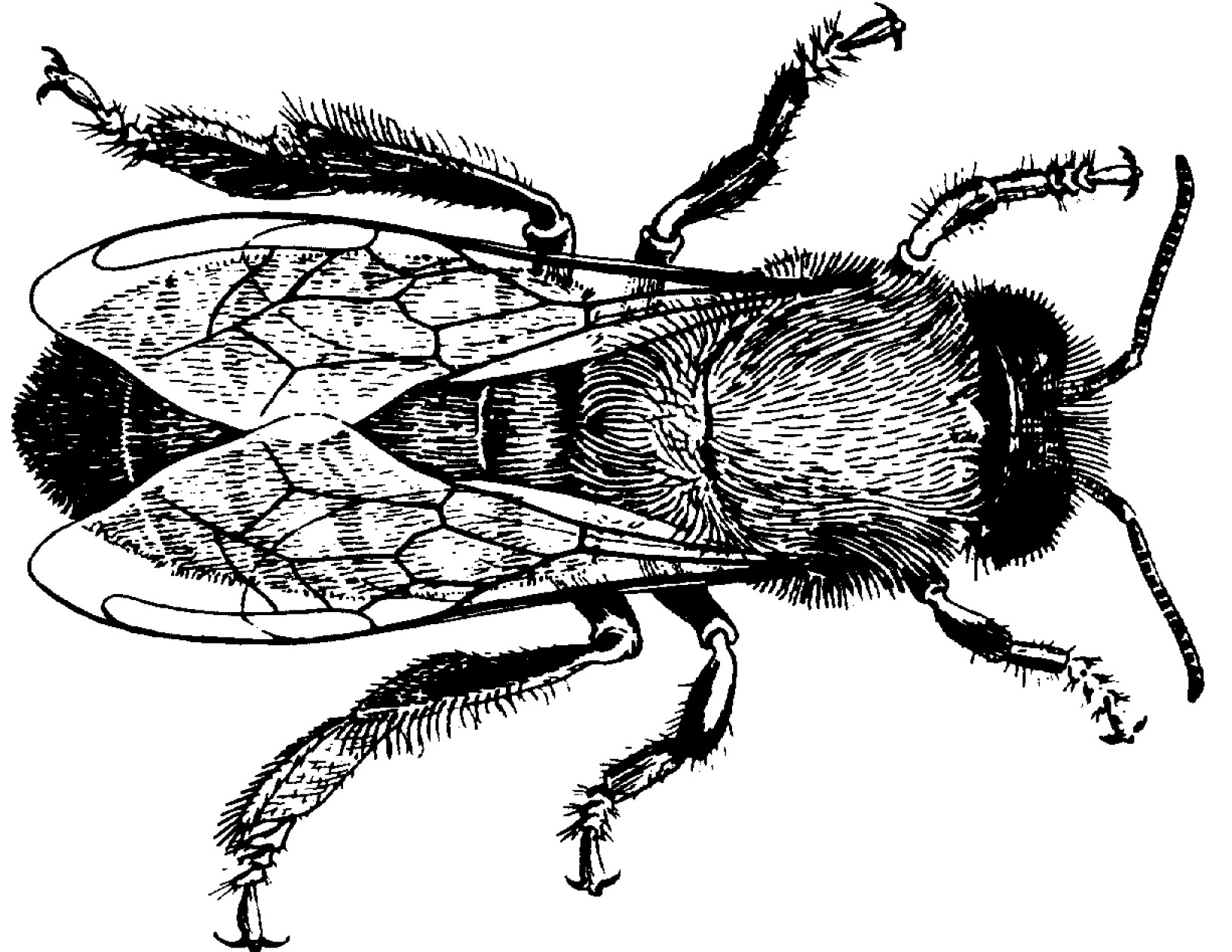

Drone

Drones are from unfertilized eggs. For those of you who studied any genetics, they are haploid, meaning they only have a single set of genes, where a worker and a queen are diploid, meaning they have pairs of genes (twice as many). Drones are shorter and fatter, have huge eyes and no stinger. The egg hatches on day 3 1/2. The cell is capped on day 10 (for large cells) or as early as day 9 (for natural sized cells) and emerges on day 24 (for large cells) or between day 21 and 24 (for natural sized cells). The colony will raise drones whenever resources are plentiful so that there will be drones to mate with a queen if they are needed. It is unclear what other purposes they serve, but since a typical hive raises 10,000 or more of them in the course of year and only 1 or 2 ever get to mate, they may serve other purposes. If there is a shortages of resources the drones are driven out of the hive and die from cold or starvation. The first few days of their lives they beg food from the nurse bees. The next few days they eat right from the open cells in the brood nest (which is where they usually hang out). After a week or so they start flying and finding their way around. After about two weeks they are regularly flying to DCAs (Drone Congregation Areas) in the early afternoon and stay until evening. These are areas where drones congregate and where the queens go to mate. If a drone is "fortunate" enough to mate, his reward is to have the queen clamp down on his member and rip it out by the roots. He will die from the damage. The queen stores up the sperm in special receptacles and distributes it as she lays the eggs. When the queen runs out, she does not mate again, she fails and is replaced.

Yearly cycle of the colony

By definition this is a cycle so we'll start when the year really begins, in the winter.

Winter

The colony tries to go into winter with sufficient stores, not only to survive the winter, but to build up enough by spring for the colony to reproduce. To do this the colony needs lots of honey and pollen. The bee colony appears to be dormant all winter. They don't fly unless the temperatures get up around 50 F. But actually the bees maintain heat in the cluster all winter and all winter the colony will rear little batches of brood to replenish the supply of young bees. These batches take a lot of energy and the cluster has to stay much warmer during them. The colony takes breaks between batches. As soon as there is any supply of fresh pollen coming in the colony will begin buildup in earnest. Usually the early pollen is the Maples and the Pussy Willows. In my location this is late February or early March. Of course if the weather isn't warm enough to fly, the bees won't have any way to get it. Beekeepers often put pollen patties on at this time so the weather won't be a deciding factor in the buildup.

Spring

By spring the colony is now building up well. They should have raised at least one turnover of brood by now. They will really take off with the first bloom. This is usually dandelions or the early fruit trees. Here in Nebraska, that's the wild plums and chokecherries which will bloom about mid April. Between now and mid May the colony will be intent on swarm preparations. They will try to finish building up and then start back filling the brood nest with nectar so the queen can't lay. This sets off a chain reaction that leads to swarming. The more the queen doesn't lay the more she loses weight so she can fly. The less brood there is to care for, the more unemployed nurse bees there are (the ones who will swarm). Once critical mass of unemployed nurse bees is reached, they will build swarm cells, the queen will lay in them and the colony will swarm just before they are capped. All of this is assuming, of course, that there is abundant resources and that the beekeeper doesn't intervene. If they decide not to swarm then they go full throttle into nectar collection. If they decide to swarm then the old queen leaves with a large amount of the young bees and try to start a new home somewhere. Meanwhile the new queen emerges in a couple of weeks and starts laying in another couple of weeks and the remaining field bees haul in the crop to build up for the next winter.

Summer

Our flow is really mostly in the summer. This is usually followed by a summer lull. It seems to be driven, here in my location anyway, by a drop in rainfall. Sometimes if the rain is timed right there isn't really a lull at all, but usually there is. Our flow starts about mid June and ends when things dry up enough. Sometimes there's an actual dearth where there is no nectar at all and the queens stop laying. I'd say most of my nectar is soybeans, alfalfa, clover, and just plain weeds.

Fall

We usually get a fall flow. It's mostly smartweed, goldenrod, aster and chicory with some sunflower and partridge pea and other weeds. Some years it's enough to make a crop. Some years it's not enough to get them through the winter and I have to feed them. Around mid October, usually, the queens stop laying and the bees start settling in for the winter.

Products of the hive

The bees produce a variety of things. Most of these are gathered from the bees by people.

Bees

Many producers raise bees and sell them. Package bees are available from the Southern United States usually in April.

Larvae

Many people over the world eat bee larvae. It is not that popular here in the US. To raise larvae (which the bees have to do to get bees) the bees need nectar and pollen. Feeding syrup or honey and pollen or pollen substitute is a way to stimulate the bees in the spring to raise more brood and therefore more bees.

Propolis

The bees make this from tree sap that is processed by enzymes the bees make and mix with it and sometimes they mix in beeswax. It is used in the hive to coat everything. It is an antimicrobial substance and is used both for sterilizing the hive and for structural help. Everything in a hive is glued together with this. Openings that the bees think are too big are closed with this. Humans use it as a food supplement and as a topical anti microbial for cuts and for cold sores etc. It kills both bacteria and viruses. Propolis traps are available. A simple one is a screen over the top of the hive and you roll it up and put it in the freezer and then unroll it while it's frozen to break all the propolis off.

Wax

Anytime a worker bee has a stomach full of honey and no where to store it, it will began to secrete wax on its abdomen. Most of the wax is then used to build comb. Some falls on the floor of the hive and is wasted. For humans, beeswax is edible, although it has no nutritional value. It is used in foundation, candles, furniture polish and cosmetics. The bees need it to store their honey in and raise their brood in. To get it from the bees, either crush comb and drain the honey, or use cappings from extracting and melt and filter them.

Pollen

Pollen has a lot of nutritive value. It is high in protein and amino acids. It is popular as a food supplement and is believed by many to help with their allergies, especially if it is pollen collected locally. The bees need it to feed the young. Pollen traps are available commercially or you can find plans to build your own. The principle of a pollen trap is to force the bees through a small hole (the same as #5 hardware cloth) and in the process they lose their pollen which falls into a container through a screen large enough for pollen but too small for the bees (#7 hardware cloth). Some pollen traps must be bypassed about half the time so the hive doesn't lose it's brood from lack of pollen to feed the brood. A week on and a week off seems to work. Other problems with pollen traps is drones not getting access in and out and if a new queen is raised, she has difficulty getting out and can't get back in. If you are allergic and trying to treat allergies with pollen take it in very small doses until you build a tolerance or until you have a reaction you don't want. If you have a reaction either take less or none at all depending on the severity.

Pollination

A "product" of having bees is that they pollinate flowers. Pollination is often a service that is sold. $50 to $150 (depending on the supply of bees) for 1 ½ deep boxes is a typical charge for pollination. Pollination charges are usually based on having to move the hives in and out in a specific time frame so that the trees (or other plants) can be sprayed etc. It is less likely there will be charges for pollination if the bees can be left there year round and pesticides are not used. In this case it is usually a mutually beneficial situation for the beekeeper and the farmer and there usually is no charge or rent either way, although it's common for the beekeeper to give the farmer a gallon of honey from time to time.

Honey

This is what is usually considered the product of the hive. Honey, in whatever form, is the major product of the hive. The bees store it for food for the winter and we beekeepers take it for "rent" on the hive. It is made from nectar, which is mostly watered down sucrose, which is converted to fructose by enzymes from the bees and dehydrated to make it thick.

Honey is usually sold as Extracted (liquid honey in a jar), Chunk comb (a chunk of comb honey in liquid in a jar), Comb honey (honey still in the comb. Comb honey is done in Ross Rounds, section boxes, Hogg Half combs, cut comb, and more recently Bee-O-Pac. It is also sold as creamed honey (where it is crystallized with small crystals).

All honey (except maybe Tupelo) eventually crystallizes. Some does this sooner and some later. Some will crystallize within a month, some will take a year or so. It is still edible and can be liquefied by heating it to about 100 degrees or so. Crystallized honey can be eaten as is also, or crushed to make creamed honey or feed to the bees for winter stores.

Royal Jelly

The food fed to the developing queen larvae is often collected in countries where labor is cheap and sold as a food supplement.

Michael Bush

Copyright 2006 by Michael Bush